Tips on Producing Great Color

Good color starts by calibrating all of the devices within the color work flow.

Devices should be calibrated often to ensure that they have not “drifted.” The frequency depends upon your reliance on color. As you know from reading this blog, calibrating brings the device to a known, stable state, and is a baseline.

Calibrating your monitor is just as important as calibrating the print device.

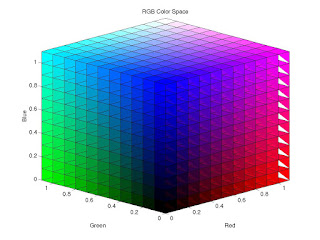

Whatever color space you might be working in, unless your monitor presents you with controlled, managed color, what you see will not match what you get. First, it’s important to think about the problem correctly. The goal isn’t to match the prints to the monitor or the converse. The goal is to make sure both the monitor and the prints reflect, as accurately as possible, the information that is actually in the digital file. There are lots of methods for calibrating your monitor, and it can get quite involved.

Here is a video showing how YOU can calibrate your monitor for FREE.

Here is a video showing how YOU can calibrate your monitor for FREE.The major manufacturers of monitor calibration packages for the casual user are Datacolor (the Spyder series ), X-Rite (the i1 series, PANTONE Huey and the ColorMunki) and Integrated Color (ColorEyes Display Pro). All these products are of excellent quality. The first two have several price levels of packages with varying capabilities.

The more expensive packages may include features you don’t need, such as printer profiling and projector calibration, and the ability to customize calibration settings beyond the defaults. The accepted standard is to calibrate to a color temperature of 6500K, a gamma of 2.2 (for both PC and Mac platforms) and a luminance of 90 cd/m2 and these will be the default setting in all the packages. But some of the less expensive packages may not do everything you need, such as luminance adjustment. Check the details.

Some laptop screens may not be able to be calibrated properly, and older or very inexpensive computers may not be able to use a profile. Apple laptops will need the ColorEyes software mentioned above.

An issue with Windows is a utility called Adobe Gamma. If it is in your Startup file it will be loaded on startup and override your calibration settings. Simply go to Start > Programs > Startup, right click the Adobe Gamma Loader and click Delete. (If it’s not there, don’t be concerned.) Don’t be nervous about doing this. It only turns it off as a startup item; it does nothing to what is installed your computer.

A custom ICC profile should be created for each device within the Color Supply Chain.

This process ensures accurate and automatic translation of color values from one device to another, minimizing time and waste during the production process. A Device Link Profile can be established to link devices commonly used in the production process, eliminating the need to specify individual device profiles each time.

Paper, inks and toner impact the ultimate color result. Creating individual device profiles for each paper type, ink and/or toner used delivers a more consistent result. For example, if a proof is being generated on a glossy, coated stock, but the final product is being produced on a matte uncoated stock, these custom profiles can produce a more consistent result.

Spot colors can add time and cost to a printed project. Not all spot colors can be faithfully reproduced with CMYK four-color process. Designers and printers should carefully consider the colors that they are using within the context of the project’s budget and desired outcomes. Many tools exist that can help users determine whether or not a special color can be faithfully reproduced using a CMYK match. It is often necessary to use spot colors to consistently match special corporate colors and to ensure absolute color consistency across a distributed printing process.

Make sure you aren't "duplicating" any colors.

This process ensures accurate and automatic translation of color values from one device to another, minimizing time and waste during the production process. A Device Link Profile can be established to link devices commonly used in the production process, eliminating the need to specify individual device profiles each time.

Paper, inks and toner impact the ultimate color result. Creating individual device profiles for each paper type, ink and/or toner used delivers a more consistent result. For example, if a proof is being generated on a glossy, coated stock, but the final product is being produced on a matte uncoated stock, these custom profiles can produce a more consistent result.

Spot colors can add time and cost to a printed project. Not all spot colors can be faithfully reproduced with CMYK four-color process. Designers and printers should carefully consider the colors that they are using within the context of the project’s budget and desired outcomes. Many tools exist that can help users determine whether or not a special color can be faithfully reproduced using a CMYK match. It is often necessary to use spot colors to consistently match special corporate colors and to ensure absolute color consistency across a distributed printing process.

Make sure you aren't "duplicating" any colors.

Look through the color palette in your page layout software. Remove any duplicate colors you find, and reassign the corresponding objects and layers accordingly.

Make sure you give your colors the same names in each application you use for the project.

Make sure you give your colors the same names in each application you use for the project.

For example, make sure you give the color the same name in InDesign as you give it in Photoshop and Illustrator. This will help reduce confusion and ensure the colors separate properly when preparing the piece for print.

Communication among all constituents in the color work flow is essential. This communication should include sharing of ICC profiles, discussion about paper and ink types and proofing models, and more. In doing so, good, consistent color can be produced across widely varying geographies and output technology types.

Communication among all constituents in the color work flow is essential. This communication should include sharing of ICC profiles, discussion about paper and ink types and proofing models, and more. In doing so, good, consistent color can be produced across widely varying geographies and output technology types.

Using a good RIP in the production process is a critical element in the color work flow. It alleviates many color issues and reduces training challenges. Consistency in settings within the RIP is key to delivering repeatable and known color.

When using digital cameras or scanners for input, if you want your colors to be consistent from shot to shot, or scan to scan, include a color target in the first frame/scan of a sequence. When it comes to processing, set the grey point (and black and white points) using the target reference frame, and your software will match the subsequent batch of images.

Always color correct images in the largest RGB color space available. When images are converted from RGB to CMYK, you lose color information—a lot of it. As a result, you (and your color management tools) have fewer colors to work with, or average, when attempting to make color changes to an image. Also, when images are converted from RGB to CMYK, you’re creating the black separation and reducing the amount of CMY in the image at the same time. Depending upon how much CMY is eliminated in the separation, it can be very difficult—or even impossible—to make color adjustments to an image.

When designing for color output, avoid large solids. While lithographic presses have the ability to reproduce solids evenly, toner-based devices have a tendency to mottle, show unevenness, or even banding. This is because ink and toner are radically different materials. When toner is applied to paper, it is dry. Toner is not actually absorbed into the paper fibers, instead, it is fused to the sheet using both heat and fuser oil, creating a bond. Consistency lies in how evenly the toner was applied to the paper, and how evenly it was fused to the paper.

If tints and large solids must be used in a design, there are some ways to help counteract the uneven appearance associated with toner-based devices. First, try applying a filter (Photoshop Add Noise or Texture filters work well) to the large tint or solids. Another option is to also break up large color areas with other design elements such as text, images, or illustrations.

Communication among all constituents in the color work flow is essential. This communication should include sharing of ICC profiles, discussion about paper and ink types and proofing models, and more. In doing so, good, consistent color can be produced across widely varying geographies and output technology types.

Communication among all constituents in the color work flow is essential. This communication should include sharing of ICC profiles, discussion about paper and ink types and proofing models, and more. In doing so, good, consistent color can be produced across widely varying geographies and output technology types.Using a good RIP in the production process is a critical element in the color work flow. It alleviates many color issues and reduces training challenges. Consistency in settings within the RIP is key to delivering repeatable and known color.

When using digital cameras or scanners for input, if you want your colors to be consistent from shot to shot, or scan to scan, include a color target in the first frame/scan of a sequence. When it comes to processing, set the grey point (and black and white points) using the target reference frame, and your software will match the subsequent batch of images.

If tints and large solids must be used in a design, there are some ways to help counteract the uneven appearance associated with toner-based devices. First, try applying a filter (Photoshop Add Noise or Texture filters work well) to the large tint or solids. Another option is to also break up large color areas with other design elements such as text, images, or illustrations.

----------

Do you have a color management question, horror story or event to share?

Email me at reilley4color@gmail.com

Email me at reilley4color@gmail.com

No comments:

Post a Comment

Got a comment, or correction? Please let us know!